BY:

Cashlite has arrived in Kenya. It just took a while

October 30th, 2025

In 2015, my colleague, Laura Cojocaru and I wrote about the digital payments revolution in Kenya that wasn’t. Based on 2012-13 financial diaries data, we showed that M-Pesa had become a very important tool for domestic remittances, but that its penetration into retail payments was negligible. Among diarists, 96% of expenditure payments were still done in cash, 3% on credit, and only 1% with M-Pesa. M-Pesa payments were confined to airtime purchases. We were a long way from any digital payment capturing the high volume of small payments that constituted the ways most Kenyans earned and spent their money.

Fast forward to 2025, and it appears the situation has transformed.

FSD Kenya, Ekko Insights, and Georgetown University have recently embarked on a new financial diaries research project, layering financial diaries with high-frequency data on health experiences. As we’ve started capturing households’ income and expenses, we’ve been surprised by how much both have digitized.

For example, one of our new diaries households in Nairobi is comprised of a boda boda rider, “Brian,” his wife, “Anne,” who does some small-scale tailoring, and their two children in primary school. Most of Brian’s revenue comes from M-Pesa, an average of KSh 1145 on M-Pesa and KSh 284 in cash each day, based on our current data. Brian almost universally pays for fuel using M-Pesa Buy Goods at the petrol station. He sometimes uses the cash he earns to buy lunch while he’s out, to pay the bike owner his daily rental fee (the owner is a neighbor), or to give Anne for shopping at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Whatever cash he has at the end of the day gets deposited on M-Pesa at a local agent.

When it comes to household expenditures, 68% of all expenditure payments this household did during our pilot phase were done using M-PESA. And they were making an average of 27 separate expenditure transactions per day, about a third more transactions by volume than our busiest urban households back in 2012/3. The median transaction size was just KSh 50 on M-Pesa vs KSh 65 for cash. Even when buying tomatoes or Royco for KSh 10, Anne often used M-Pesa. It made sense, because Brian usually sent her shopping money on M-Pesa, and because transactions under KSh 100 on M-Pesa had been zero rated since 2016.

Another pilot household behaved very similarly, albeit with lower income levels. When this respondent was sent KSh 500, she wanted to put aside all of it to save up for an electric kettle. She sent the money – KSh 100 at a time – to a friend who had cash, effectively withdrawing her funds without ever visiting an agent and paying no transaction or withdrawal fees.

We are just a few weeks into diaries in other parts of the country. While in some areas, expenditures are mostly in cash, we are still seeing extensive use of M-Pesa going well beyond remittances, even in remote rural areas.

What happened?

We don’t have a full picture – at least not yet – but some key dynamics are clear.

- Low-income people are price sensitive. The removal of transaction fees for small payments has clearly played a major role in the increased use of M-Pesa for small purchases and retail payments. By zero rating low-value payments, Safaricom met users where they were. They made it possible to keep transacting as usual, just changing the channel. They could still buy easily, digitally from one another in the vast informal economy. They could still purchase what they needed in very small values. We found back in 2012/3 that the median transaction size for cash payments was just KSh 40, quite similar to Brian and Anne’s typical expenditures on M-Pesa today. According to Safaricom’s most recent Annual Report, non-chargeable transactions represent about 42% of all M-Pesa transactions. Revenue growth on M-Pesa has been strong in spite of this large volume of free transactions. Perhaps zero rating of small payments created a more compelling reason for more Kenyans to keep their digital money digital and that this is paying off in terms of customer revenue overall.

- More extensive payments usage is seeding wallets. When ordinary people are paying for small transactions using M-Pesa, they are effectively digitizing the incomes of their neighbors running small kibandas, shops, bodas, or doing vibarua (casual jobs) on their behalf. This appears to be creating a cycle of digital payments, some of which are If digitization had come on any channel that wasn’t led by person-to-person payments, digitizing incomes in the informal sector would have been an uphill battle if not an impossibility.

- Retail payments are not just on retail payment M-Pesa channels. The powerhouse of M-Pesa payments in this market remains “Send Money.” It’s just easy that way. When Anne buys onions and tomatoes, she uses Send Money at her local kibandas. Brian’s clients primarily use Send Money, too, unless he thinks there’s a risk they might try to reverse the payment, in which case he directs them to use Pochi la Biashara. He registered for a Till Number (“Buy Goods”) when Safaricom did an activation in the area. But ever since, he only put KSh 10 as a test and never used it again. Not needing to jump through extra KYC hoops to get an M-Pesa for business account nor buying any POS devices, means that the digital transition we’re seeing has been truly inclusive, with acceptance quickly ubiquitous. Even the smallest vendors of vegetables and mandazi have not been left behind.

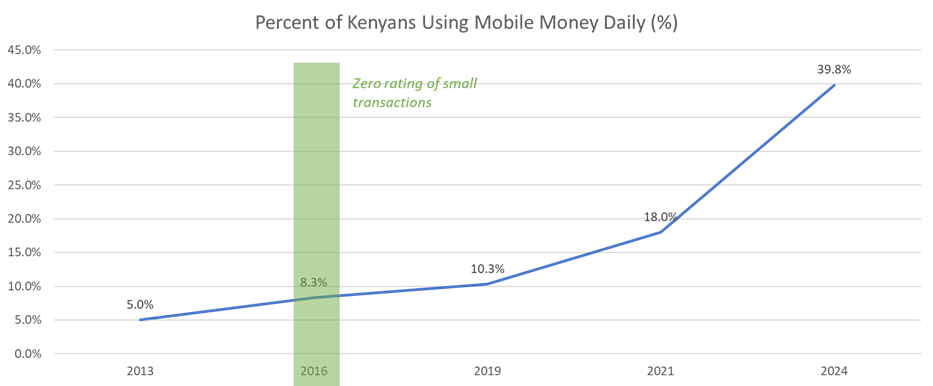

- Transformation took catalytic policies and time. FinAccess 2024 reported that daily usage of M-Pesa among users jumped from 23.6% in 2021 to 52.5 % in 2024. That means nearly 40% of all Kenyans are using M-Pesa daily. This widespread high-frequency usage was hit eight years after small transactions were zero rated. This suggests there were other factors at work. I suspect it was a function both of policy catalysts and time.

Part of the acceleration we see is between 2019 and 2021, straddling the Covid era. Having done a lot of fieldwork during that period, it is not my impression that people were overly concerned with virus transmission via cash. However, two covid-driven policy changes likely did have an impact. First, the Central Bank paused bank-to-M-pesa fees, allowing especially higher income users to fuel their wallets and drive transactions. Safaricom also temporarily extended the range of free payments up to KSh 1000.

While these policies were likely important catalysts to the change in digital payments, growth in daily usage seems to have continued even after those policies were rolled back. Here, time may be playing an important role, helping entrench the culture of digital payments.

Figure 1: Daily usage of M-Pesa among all Kenyans over time. Source: Author’s calculations based on FinAccess data over time.

Do ubiquitous digital payments make people better off?

Has increased payments digitization led to increased utility for ordinary people? To fully answer that question, a more carefully designed study would be needed. So far, our respondents’ haven’t reported obvious, outsized benefits. There may be some small convenience gains for those receiving money digitally in their work to be able to turn around and spend that money digitally. The rise of digital payments has coincided with a shortage of coins and small bills to make change, which may be adding some friction to cash payments in some areas. Still, it’s not clear that these more extensive digital trails are doing things like leading to new lines of credit, credit that better meets users’ needs, or that is lower cost. It’s not obvious that money held on M-Pesa is safer or easier to save.

But there is one other change worth noticing. It appears that with small payments over “Send money” normalized, affordable, and ubiquitous, we are seeing more smaller P2P transactions in our households. Rather than sending his sick stepmother a larger sum once a month, Brian sends small values, even KSh 200, when there’s something she needs. It is rare he goes a whole week without sending something. Instead of receiving KSh 2000 for shopping for the month, respondents are reporting getting KSh 150, for “breakfast” or having KSh 100 sent directly to the pharmacy to immediately pay for medicine. In other words, the immediacy of individuals’ ability to make claims on their social network seems to have gone up and the value thresholds for helping out appear to have gone down, leading to what might be even more extensive networks of sharing and coping, which are likely particularly useful in what have been some difficult, volatile economic times.

More to learn

All of this is based on early work in the new HealthFin Diaries. There is so much more we hope to learn on this topic as the work continues through 2026:

- How do these trends compare in various rural and urban sites across the country?

- Who are the biggest adopters of digital payments and which types of people are more likely to still be using primarily cash? Why?

- How much revenue are various types of customers generating for payments service providers?

- Just how much are specific retail payments options like Buy Goods, Pochi la Biashara, and Paybill penetrating lower-income segments, and what can others learn from this?

- What value – and what risks – are various types of individuals experiencing in this new payments landscape?

We think there’s more to unpack here that will matter for Kenya’s payment future and for other markets with similar dynamics where cash remains king.

This blog was first published on Development Ekko.